Face First:

How New York’s Facial Recognition Tech Is Fueling a Real-Life Orwellian Debate

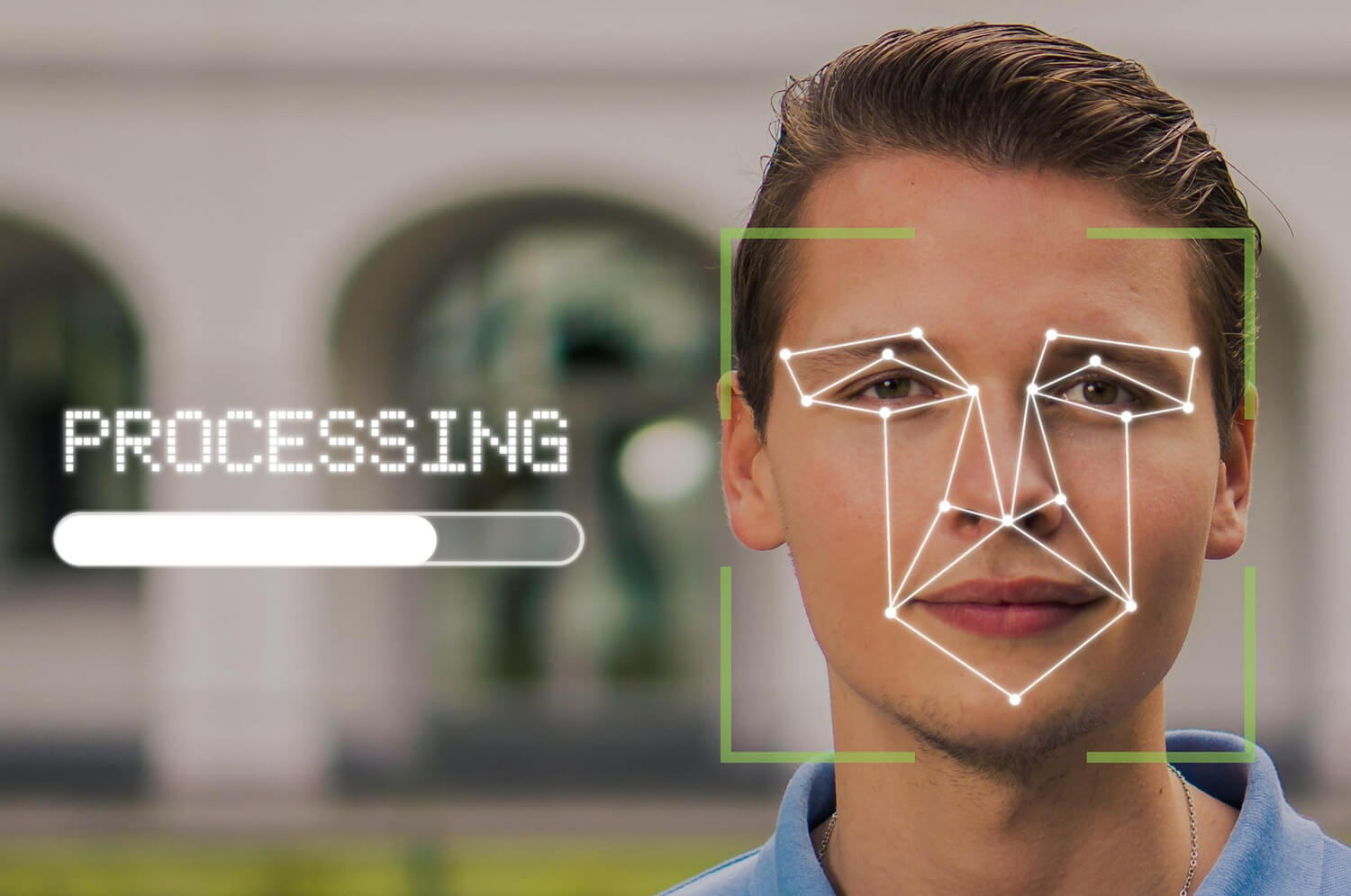

It was only a matter of time. The same facial recognition software that unlocks your phone and tags you in Instagram posts is now showing up in schools, subway stations, and public spaces across New York . . .and it’s raising some serious “Big Brother” energy.

The technology promises safety, security, and convenience. But what it’s delivering, many argue, is something far more troubling: a surveillance infrastructure growing faster than the rules meant to govern it.

A few years ago, the Lockport City School District in western New York became one of the first in the country to install facial recognition cameras in its schools. The idea was to prevent threats by identifying suspended students, keeping out people flagged as dangerous, and offering a real-time alert system for campus safety. It sounded high-tech and proactive. But almost immediately, the backlash rolled in.

Parents, privacy advocates, and educators pushed back, calling the system invasive and unnecessary, especially in an environment meant for children. Civil liberties groups argued that it normalized biometric surveillance in public schools, and concerns mounted over the accuracy of the technology, especially when it came to identifying people of color and young students whose features change rapidly. By September 2023, after mounting public pressure and a wave of concern about the broader implications, New York State stepped in. A statewide ban on facial recognition in schools was issued, making New York the first state to slam the brakes on student surveillance in such a definitive way.

But the story doesn’t end there.

In New York City’s subway system, facial recognition had been quietly tested by the MTA for years. Officially, the agency claimed it was evaluating how the tech could improve fare enforcement and reduce fare evasion. But civil rights groups raised alarms over what they saw as a slippery slope, one where every trip through a turnstile could feed into a massive biometric database. In April 2024, New York lawmakers responded to public concern and passed legislation banning the use of facial recognition for fare enforcement. Riders breathed a little easier, but the larger issue loomed: where else is this technology already watching us?

The NYPD has integrated facial recognition into its powerful Domain Awareness System, which includes over 9,000 cameras spread across the five boroughs. Officials insist that the system is used responsibly, that it helps track down suspects and prevent crimes. But critics argue that the surveillance net is too wide and too opaque. Who’s being tracked? Where is that data going? And who gets to decide what’s done with it?

That last question is particularly important, because the public doesn’t really know where much of this biometric data ends up. It’s often stored in centralized databases managed by the agencies or the private tech companies that power the software. And while most official uses are supposedly limited to law enforcement, experts warn that without strict oversight, there’s potential for data to be shared, hacked, or even sold. After all, some major retailers already use facial recognition to identify shoplifters and they’ve faced lawsuits for doing so without informing customers.

The fear is that what starts as crime prevention could easily morph into something more sinister: profiling, unauthorized surveillance, or even discrimination based on biometric markers. Facial recognition tech is notoriously less accurate when identifying people of color, women, and nonbinary individuals. Misidentification isn’t just embarrassing, it can be dangerous.

Meanwhile, the private sector isn’t standing still. From Madison Avenue storefronts to sports stadiums, facial recognition is showing up in places you might not expect. In some retail spaces, your face could be scanned the second you walk in, compared against a database of flagged individuals, all without your knowledge or consent.

The current patchwork of rules around FRT in New York is trying to play catch-up with the speed of the tech. While bans in schools and transit systems show that regulators are listening, the broader legal framework is still evolving. There’s no comprehensive state law that regulates how facial data can be collected, stored, or shared across public and private sectors.

Advocacy groups are demanding stronger protections, more transparency, and, most of all, public accountability. The public deserves to know when they’re being watched, why, and what happens to that data after the fact. Until those questions are answered, the fear is that facial recognition won’t just be used for safety, it’ll be used for control.

So yes, we’re living in a time where walking down the street in New York might put your face into a government database. Whether that helps prevent crime or opens the door to dystopia depends entirely on how, and if, regulation can keep up with the machines. Because one thing’s for sure: Big Brother isn’t coming. He’s already here.